EXECUTIVECARE* STANDARDS

ExecutiveCare*

Standards

ISIS AWAD

Executive Care* (EC) is a curatorial initiative whose mission is to revolutionize arts patronage for early-career artists, curbing exploitation and stimulating the growth of a supportive arts community that shares its resources with those who have historically been denied them. Having worked within the nonprofit art sector in varying capacities for almost a decade, Isis Awad founded EC in New York in 2020 to address what she felt pre-existing structures of support were currently lacking. EC is a labor of love guided by the core principles of care, trust, slowness, and mutual aid. It serves marginalized and under-valued artists with a special focus on trans and queer artists of color from underground and nightlife communities whose work is often overlooked or tokenized by mainstream art institutions.

MARTA: Could you tell me a bit more about how Executive Care* emerged, and what this project means to you?

ISIS: EC emerged at a point in my career where I was severely disillusioned by the art world. I wanted to imagine how care could be implemented and instituted as a practice and core value within art organizations, as opposed to a flat concept that is unanimously agreed upon. Care is such a hot topic in the arts right now, especially within the nonprofit sector. I am interested in moving beyond performativity, and deeply thinking about how we can actually implement care as a day-to-day practice.

The founding of EC also concretizes a shift in my own perspective from curator as instigator and project proposer, to curator as caretaker and assistant. Personally, it marks my own awareness and acceptance of service-oriented labor as primary labor. Practically, EC began by serving as a sort of agent to my friends who are artists: helping them navigate proposals they received from curators and galleries; assisting them with writing and editing grant and residency applications; and advising them curatorially with ongoing projects.

MARTA: There’s something about the way you describe Executive Care* that highlights how language plays a key part in its formation. How can language be grounded in care?

ISIS: Language is integral to EC’s mission and operation. Since EC’s projects are heavily reliant on long-term collaboration and trust, contracts, or Consensual Agreements, become EC’s love-language, as we call it. The unfortunate reality is that artists are often the ones left to bear the consequences of abrupt changes in plans or budgets. This is especially true in nonprofit art contexts where a desire to be non-hierarchical is not always met with a functional alternative, leading to ad hoc solutions that only cause artists and art workers more stress. EC is my effort to bring some executive realness to curatorial practice. Not only do these Consensual Agreements outline EC’s responsibilities and, in turn, what we expect from the artists and organizations we partner up with, but they also function to instate and legitimize our core values as professional working standards. Consensual Agreements perform a coalition-building function as well, by serving as mediums to spread EC’s Care Standard.

MARTA: When did you come to realize the importance of contracts?

ISIS: For artists, there’s no real training on how to function within the art industry. Even graduate schools don’t necessarily teach artists how to deal with an institution who has approached them to show their work in a group exhibition, for example. Especially when you’re an artist in the early stages of your career, it’s difficult not to say “yes” to offers before getting a complete picture of the situation for fear of missing out on any opportunities. We don’t talk enough about the social pressures of “quietly” agreeing to things which unfortunately end up being exploitative situations. Exposure does not pay bills. EC is trying to curb all these potential pitfalls through our Consensual Agreements and by holding space for open communication with our collaborators way beyond a project’s timeline.

MARTA: It’s the language of the art world, made of half spoken, half written proposals that somehow, we end up signing off on. This is an embedded exploitation mechanism, and it is done on purpose.

ISIS: I think it is also fueled by the shunning of corporate language or anything perceived to be slightly akin to corporate behavior by art institutions, under the guise that arts and culture work is radically above that. Why is it rare for nonprofit art organizations or galleries to have functional HR departments? As we all know, structures already exist, commonly adopted by other industries, that were created precisely to curb exploitation. This is not to say that having an HR department is the only solution, and maybe the answer to that question is rooted in a lack of funding. But then again, I believe that it is the art institution’s responsibility to be aware of those needs and to communicate them with their funders. This “better than” mentality is what ends up mystifying the labor of artists and art workers under the belief that art work is “for the betterment of society,” when the reality is that the people doing the work often feel overworked and underpaid. But I do believe that a shift toward creating more caring structures within art institutions is slowly approaching. You see it now with museums like The Met hiring their first Chief Diversity Officer, for example, and more funders adopting a basic income model. As our manifesto says, EC registers how the intentions of such structures could be applied to our purpose, our goals, and our operations.

MARTA: How would you describe arts patronage in relation to Executive Care*?

ISIS: EC’s main mission is to revolutionize the way that artists, especially those in early stages of their careers, who don’t have access to generational wealth, are supported. Our goal is to offer artists production support in the form of monthly unrestricted stipends, curatorial guidance, and access to mentorship over an extended period of time, which leads up to public exhibitions of their work. Based on the grants I have helped my friends apply for and my own experiences applying to grants for institutions in different contexts, I find that funding comes too late. There is this working assumption that the artwork has already been made, which is not always the case. Of course there are grants which support artistic production, but a lot of them, if not all of them, don’t cover expenses retroactively, which leaves many artists in debt. Moreover, grants are often merit-based and expect artists to upload multiple samples of their work in order to qualify. What about artists who do not have the generational wealth or the support to make art consistently, or on a scale that makes them competitive for these opportunities? How, as an artist, is one expected to have work samples to upload in support of a production grant application, when one needs the production grant to make that work in the first place? EC also suffers from the same paradox. As an art organization, we are expected to have an ongoing program of exhibitions and events in order to attract and secure support from foundations and funders, yet without that support, how are we expected to produce programs and exhibitions? This speaks to the glaring lack of arts and culture organizations founded and run by marginalized people of color.

MARTA: It’s a system built to support people that already have a certain security and have access either to wealth or have a solid network within the art world.

ISIS: And if you look around that’s really it. The artists that are able to continuously make new work, invest in their practice, and create a succinct body of work are artists that have some kind of support because the fact is making art requires a lot of time and money, and artwork has historically always been patron-supported.

MARTA: Especially if you are living in a city like New York, which is extremely expensive.

ISIS: And add to that, the structures that exist privilege those who already have access to space and visibility. It becomes extremely hard, if not impossible, for artists who have historically been denied equal access to employment and housing because of their marginalized identities to take advantage of the existing arts patronage system.

MARTA: The question of accessibility is one that is most urgent, yet the most enduring, within the arts sphere. What models of support, financial and institutional, have you set up to tackle accessibility? How does EC differentiate itself from other nonprofit arts organizations that might share, at least in their mission statements, similar notions of support and care in regards to artists?

ISIS: I think what makes EC’s model slightly unique is its focus on serving queer and trans artists of color from performance and nightlife communities. By offering access to monthly monetary and mentorship support over an extended period of time, we hope that this will enable these artists to have the freedom to experiment, make artwork, and survive. It is ironic and sad how we as queer and trans people are often met with rejection and a withdrawal of care from our immediate families and the support systems we were born into, even though we are the groups who need that unconditional love and support the most. Our goal, for starters, is to be able to provide ongoing support for two artists per year in the form of monthly unrestricted stipends of $1000; and to support the public dissemination of their work at the end of that year through exhibitions, programs, and publishing. These stipends can be used to cover any kind of cost, and artists would not be asked to report back on what they were put toward. The hope is that this model will supplement income, or lack thereof, allowing artists to dedicate more time and energy to their art practice.

MARTA: Safe spaces for queer, marginalized communities are needed now more than ever. Historically, underground nightlife has always been at the center of it. What’s the potential that nighttime holds for you?

ISIS: For myself and many members of the trans and queer community, nightlife is just life. Night time and night spaces are often the only options for us to exist together in space, somewhat freely. And to be honest, even within queer-run, or “queer-friendly” parties and spaces, safety is never guaranteed. The reason why EC focuses on supporting artists from performance and nightlife communities is because these are the communities that I myself am enmeshed in and who need support the most. And although I believe in the generative and revolutionary potential of the party and nightlife, I am aware of how disruptive and isolating working in nightlife can be, especially for those who depend on nightlife work as their only income.

Nightlife was hit very hard by the pandemic. The whole industry—venue owners, tech crews, artists, performers—are just starting to slowly recover from the incredible loss of the past two years. From a trans perspective in particular, the club or the party also provide a necessary sense of belonging and validation for us. Unfortunately, there aren’t a lot of spaces for us to go where we can feel a sense of belonging and just be.

MARTA: Can you tell me a bit more about how you’ve built your relationship with the artists EC has collaborated with so far?

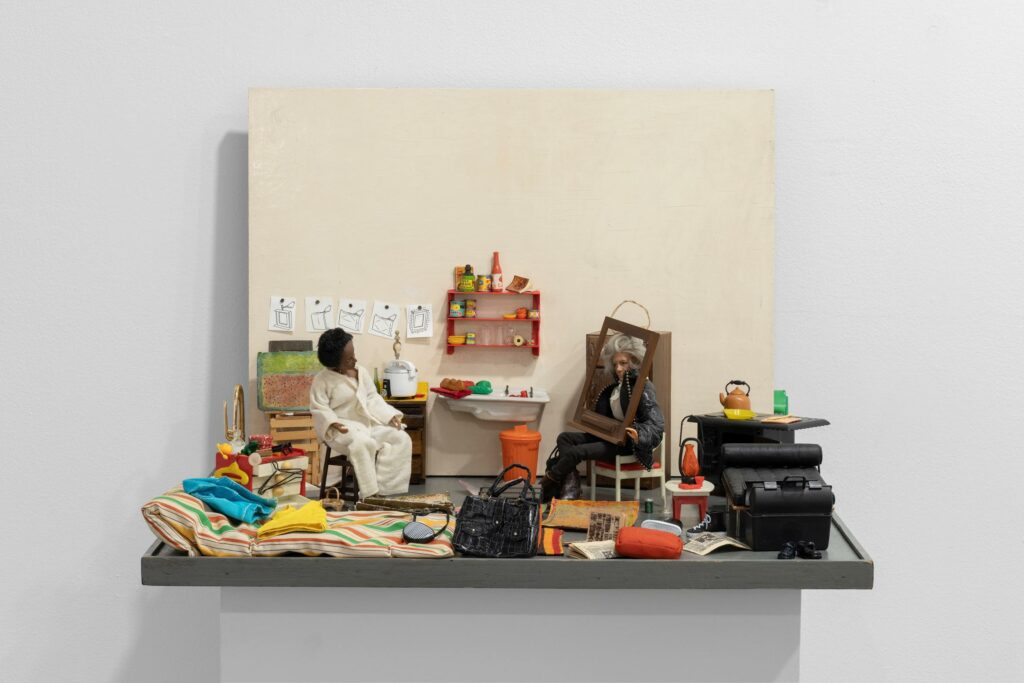

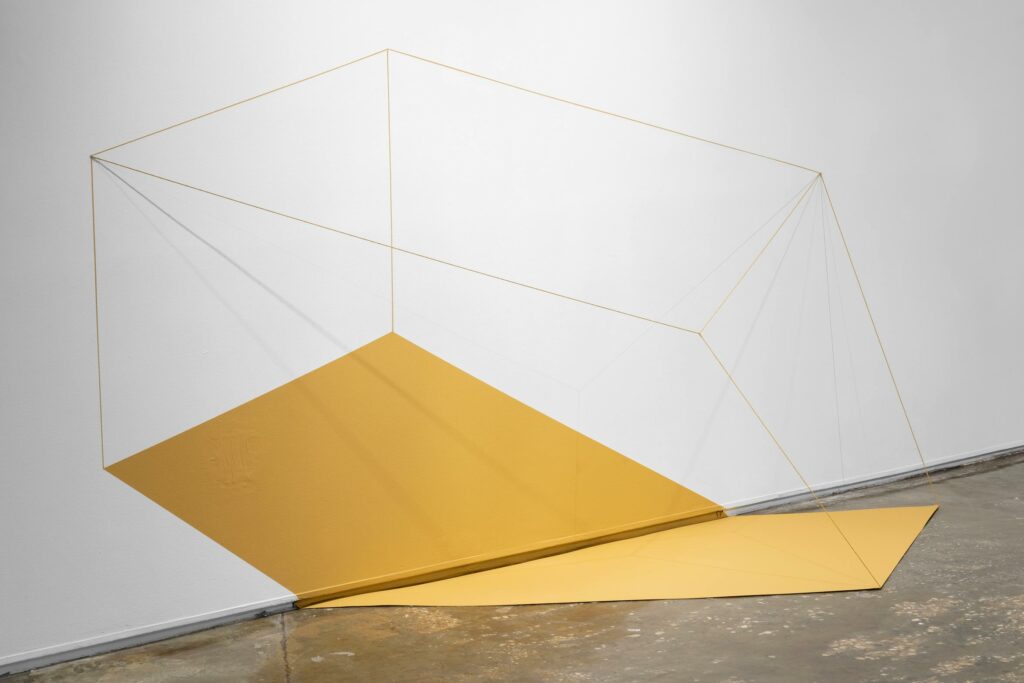

ISIS: Last summer EC launched with Brooklyn-based performance artist (and current EC board member) Keioui Keijaun Thomas’s first solo exhibition, Hands Up, Ass Out, which was hosted and supported by Participant Inc. The exhibition was the result of a two-year collaboration, showcasing a body of work spanning the last six years of the artist’s career, and included archival material from past performances as well as sculptures and prints. Thomas and I actually met at a bar and club in Ridgewood, Queens, called Nowadays, where Keioui was working the door and where I recently started operating the lights. Parties there or like the ones at The Spectrum/Dreamhouse live up to the name of a party as a community space as well as a performance art space since they have a lot of performances programmed into their party night. Since working together, Keioui has become like a sister to me, and that model of reliability and friendship is what I aim to bring to all levels of EC’s operations.

MARTA: …one of the last times I saw you was on a dance floor at The Spectrum/Dreamhouse, just before I left New York. And now, three years later, I think you have successfully translated into the art context what has always felt vital for you—in the literal sense, in the way that it makes you feel alive—by creating a curatorial platform that allows you to work with people that you care for. In a way that, unfortunately, is very rare to encounter. Making an artist feel protected, taken care of, and giving them the freedom to experiment is essential work.

ISIS: I haven’t really thought about it like that, but, yes, I guess that’s true. The same values that I respect, honor, and cherish about and from nightlife, are what I am emulating curatorially through EC. By hosting EC’s programming at and with partnering art spaces and venues, my hope is to also stimulate the growth of a supportive arts community here in New York.

MARTA: Friendship, as an essential supportive care structure, could be used here as it seems to sit at the core of this project. How would you define it and what does this word mean to you?

ISIS: I love that you bring up friendship because I was thinking about that a lot while formulating EC’s language. I thought a lot about care workers, counselors, therapists; services embedded in care that we pay money to access. I asked myself, does paying for those services demonize that care? Does monetizing care affect how genuine it is? We tend to think that things are less genuine when they are paid for and transactional, especially when it comes to love and friendship. But neglecting the time, energy, and resources needed to maintain basic survival—so that we can have the energy and capacity it takes to care for ourselves and each other—can also inhibit these relationships from ever forming. The idea of forever and unconditionality are just false notions stemming from patriarchy that in my opinion end up draining relationships. It took me reevaluating how I perceived friendship within my own life to understand that structure, order, and limitations are not detrimental to love—they could be helpful, and essential for a long-lasting, and fruitful relationship to thrive.

MARTA: The illusion that the nonprofit art world is somehow above capital, at least at a moral or ethical level, while it functions in a hyper-capitalist configuration, spreads like poison. There is this complete rupture between what you want people to think about your institution (idealistic statements), holding certain principles, and the reality of the day-to-day management operations within it.

ISIS: Exactly. We need to debunk the harmful notion that struggle breeds creativity. Instituting care functions then as an antidote against the exploitation of artists, and to dismantle the shadowy figure of the precarious art worker, suffering in the background.

MARTA: Slowness as a methodology is definitely something that we both embrace. How can we support this model of working against the grain of capitalist models to allow for a more thoughtful, responsible, and liberating way of working? What does this model need in order to thrive?

ISIS: Firstly, by understanding that art making is not a solitary occupation. It requires long-term access to time, money, space, and community guidance. What EC is offering is an artist-centered support model. The inspiration for this model actually comes from the so-called Golden Age of film, where production studios would contract actors for five to seven years at a time, and, regardless of whether they were in a production or not, they would receive monthly salaries, just like regular employees.

I want to invest in artists who are my kin, whose work I might have seen at the club, or that I know have a painting practice but don’t have the time or money to rent a studio and pay for art supplies because they are working all the time to cover bills. I am deeply invested in them not as content producers, but as people, as peers, as sisters. Right now, I am working toward incorporating EC as a nonprofit in order to gain access to more government and foundation funding, but at the same time, I could totally see EC evolving into a different kind of model. Perhaps in the future, it could embody a for-profit gallery model, with a roster of artists that receive a monthly salary no matter if they have a show on or not, and when they have one, they get extra support.

MARTA: Hence the asterisk?

ISIS: The asterisk in Executive Care* is a reflection of how mutable EC is in form and model. It signals its identity both visually and textually. I think the asterisk can become a tool to queer and redefine language, and EC’s mission is to redefine what it means to be caring in a professional context.

MARTA: Talking about physical shows—EC does not have a space, right?

ISIS: As of now, no. Being tied to renting out a space and having it empty because of COVID, or whatever else the future will hold for us, seems an unnecessary risk to take. It also allows EC to funnel more resources directly to the artists. Exhibitions and programs are hosted with partnering institutions. This collaborative exhibition model also creates space for slowness and flexibility to guide EC’s programming structure as we navigate our current precarious reality. Besides, being a space-less institution also holds multiple coalition-building functions. By connecting artists to other like-minded art organizations, we provide them with a larger network while simultaneously building a system of support between different art spaces, which are truly connected to each other and not just temporarily collaborating together in order to share funds for a specific project. As such, EC is not a monolithic tree trunk, but a catalyst stimulating the growth of different root systems and providing the infrastructure for them to communicate and feed one another.

MARTA: It strikes me that you describe EC through the use of ecology.

ISIS: There is a principle within ecology that says that the more diverse an ecosystem is the more it is able to survive disruptions. This model supports diversity not just in terms of leadership—myself and the board that I am working with—but also the artists and the spaces I will be working with in the future. I am trying to enrich and diversify the parties that have a stake in this model.

MARTA: But this is also the challenge, right? How can you make sure that an institution actually cares and shares your core values?

ISIS: I believe there are already institutions that care for the artists they work with in a way that aligns with EC’s standards. For example, Participant Inc., where we hosted our first exhibition, is an extremely supportive life system for us. Lia Gangitano, Participant’s founder, is now a member of the board and they are also our fiscal sponsor until we achieve our own nonprofit status. Another example is Visual AIDS, a nonprofit organization dedicated to serving artists who are living with HIV or have passed due to HIV-related complications. They are the only organization in New York doing this essential work. They also don’t have an exhibition space of their own, but still support guest-curated exhibitions and host their programming at different venues. These are just two examples of art organizations that EC would love to continue working with.

MARTA: What’s next then for EC?

ISIS: I’m very excited about the upcoming programming we have in store. I am focusing all my efforts on fundraising and development at the moment. And toward incorporating EC as a nonprofit. However, until that point and as I previously mentioned, we are thankful to have the fiscal sponsorship of Participant Inc., which means that we can currently receive tax-deductible donations from foundations and individuals interested in supporting our mission and programming. As much as we need diversity in arts programming, there is a real need to invest in organizations managed and led by diverse arts workers, supporting different kinds of leadership that do not quite exist in the arts yet, like ours. I’m the only one working at the moment. I myself need to be mindful of supporting myself in order to continue building a foundation for EC, as I myself don’t have access to generational wealth but I’m choosing to invest in myself and this so that I can continue and be compensated for my labor. I’m going to keep on going, things are happening regardless and are going to keep happening. I’m not going to let anything stop me. If anything, I’m motivated by feeling I need to knock louder.

Executive Care*’s non-commercial operations and programming rely solely on generous gifts from friends, and foundations. All donations to EC are fully tax-deductible, and fiscally sponsored by Participant Inc., a registered 501(c)(3) educational corporation in New York. If you want to make a donation, visit www.executivecare.art/support.

Executive Care*’s non-commercial operations and programming rely solely on generous gifts from friends, and foundations. All donations to EC are fully tax-deductible, and fiscally sponsored by Participant Inc., a registered 501(c)(3) educational corporation in New York. If you want to make a donation, visit www.executivecare.art/support.

Published 18.03.2022